Introduction

There is a lot of money to be made in the next five years from the simple thesis that China and the US will become more like each other. The irony of the superpower decoupling is that each will be forced to borrow elements from their geopolitical rival - particularly those they find ideologically distasteful - to remain competitive.

The US will need to reinvest in heavy infrastructure and subsidize the return of strategic industries while forgoing consumption and welfare expenditures to make these investments fiscally palatable. China meanwhile seems likely to be forced, against its will, into a greater liberalization of its economy as key export markets seek to rebalance.

On a host of dimensions, the next five years will see the US become more like China and China become more like the US. Due to their starting points on opposing sides, this convergence seems like it will be more favorable to Chinese equities than its US counterparts.

China spent decades suppressing wages and investing in its foundations. These deep roots are now starting to bear fruit. As large export markets turn hostile, the logical next turn is inward; stimulating consumption and encouraging more robust domestic capital markets. The US, on the other hand, has overconsumed and underproduced. It has been on harvest mode for 25 years, and now must reinvest in its foundations.

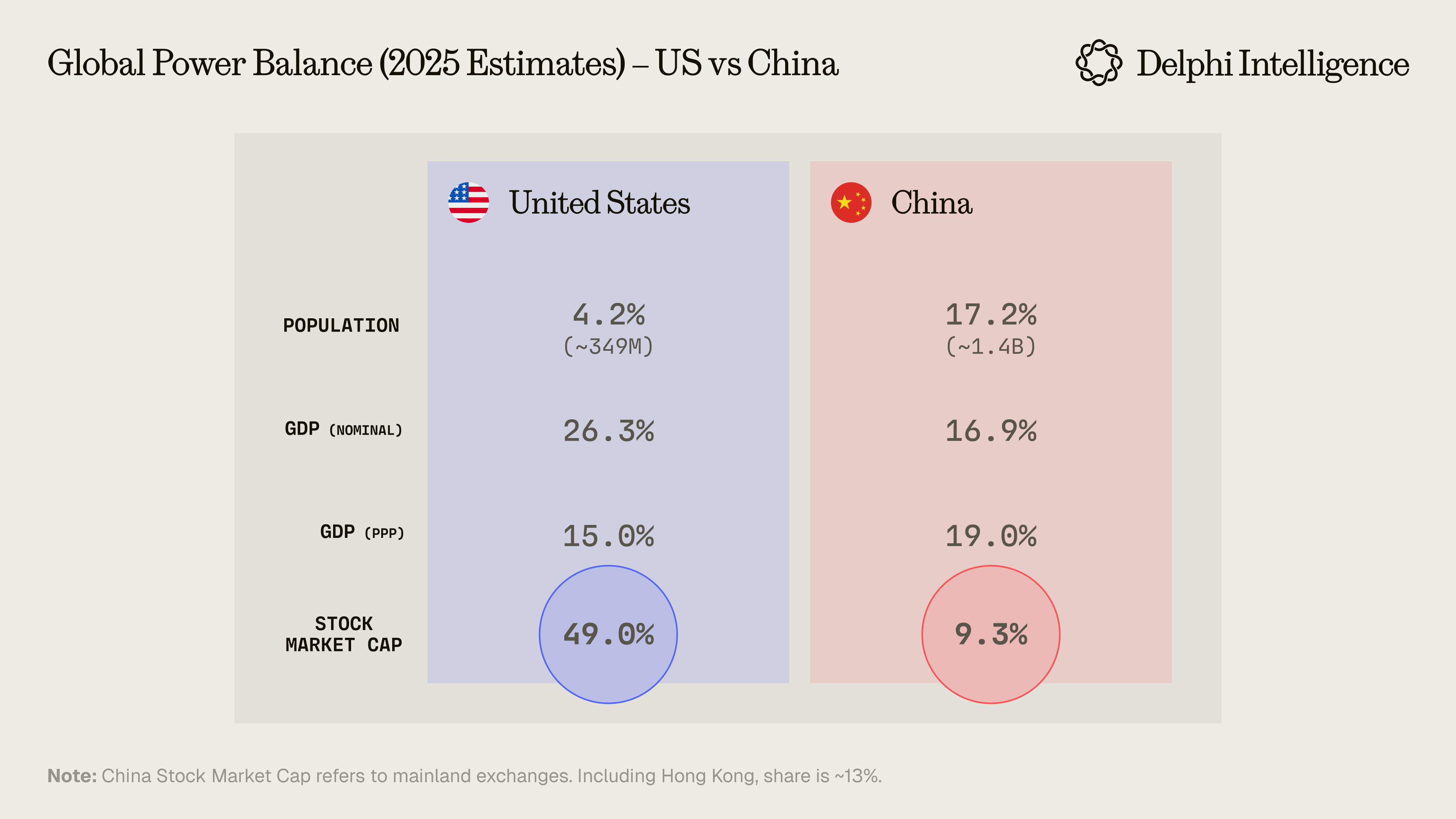

For convergence to happen, which seems probable given the unwind of the current order and each side shoring up deficiencies, it seems likely that the RMB would appreciate and the relative size of Chinese equity markets compared to the US would need to grow materially.

In short, to remain competitive, the US and China will need to become more like each other. However, because of their different starting points, the process for each will be quite different.

The Grand Bargain Unwinds

I sometimes view the US and China like Anikan and Obi wan Kenobi. Previous partners, turned by fate, now stuck in one of those Yugio-style force pushes - straining - each sliding backwards, the U.S. towards a hot, steaming lava pit (inflation), China towards a frigid icy abyss (deflation).

The world's factory and the world's consumption engine face inverted impacts as they seek to disentangle the supply chains on which the modern world is based.

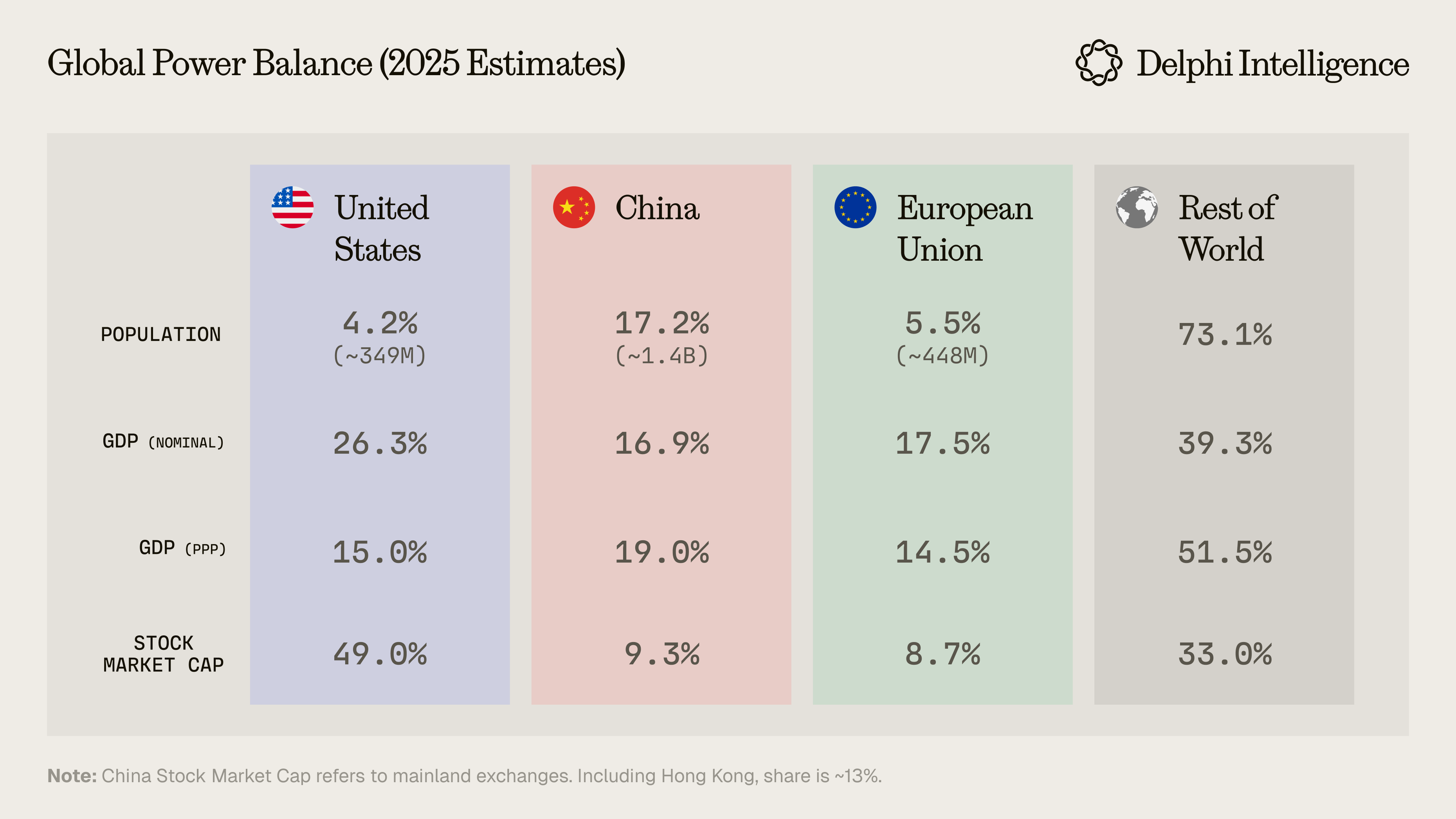

China had invested in the productive capacity to serve the world and now finds itself facing trade barriers from two of its largest customers (the US and EU combine for ~44% of world GDP). Carving out China's own domestic market, that leaves only ~39% of global GDP. The resulting excess capacity drives down prices at home and in markets which remain open to Chinese goods. The US, now keen to diversify production from its chief geopolitical rival, finds itself with rising import costs and inflating debt-service costs for its runaway deficits (fn: as large export economies rethink their historical recycling of surpluses into treasuries) - impacting prices ranging from Temu trinkets to mortgage rates.

The cost of the breakup in the US is inflation. The cost of the breakup in China is deflation. In both countries, the impact is being disproportionately shouldered by the youth.

The Lava Pit & The Abyss: the RMB is undervalued

It's been interesting living in Shanghai this year and watching the cost of living crisis in the U.S. come to a head. When I return and pay US$150 for an Uber in from JFK and fork out US$20 burrito, I can sympathize. Pulling up my "DiDi" app (the uber equivalent) for a trip to Pudong International Airport from XuJiaHui (farther than Manhattan to JFK), I am quoted 136 RMB for the trip. At today's exchange rate, this is ~US$20. The car which would take me there would likely be a new, affordable electric vehicle, traveling on paved highways which often make the Spaghetti Junction of my youth (of Atlanta interstate highway fame) appear parochial.

I stay in one of the most central parts of Shanghai - XuJiaHui - near the French Concession. Shanghai is less dense than Manhattan, but I would say a rough comparable would be staying in Union Square. We live on the 30th floor of a high-rise in a four bedroom apartment. The unit is on the older side for Chinese construction but has multiple door men and a nice xiao qu with a kid's playground inside the community. Again, this is in a very central location. This unit cost about US$4000 per month to rent last year. This past year, we negotiated down to ~US$3000.

My gym is brand new - not quite Equinox quality, but close. All new machines, full weight sets, trainers with stretching facilities, showers, automated lockers. I pay roughly US$50 per month after incentives. I suspect the tenant can price this low because mall owners are now often providing one, if not two, years of free rent to entice tenants to keep the property full amidst the real estate slowdown. Again, this is in central Shanghai, right off XuJiaHui park.

I generally go to a community center for breakfast. These are public facilities with a cafeteria, a library, a place for older folks to congregate. The average age in the cafeteria is probably 65+. This one has a gym, a health clinic, and therapy center. I eat at the cafeteria most mornings and typically order two niu rou bao's (think meat buns) for breakfast. Each is ~40 cents. I believe the food is subsidized. For lunch, I may go for Wontons (10 for 15 RMB, a little over US$2) or go for a Taipei-style rou bing (kind of like an Asian Burrito) for 26 RMB (a little under US$4). Both are made fresh and delicious.

When I get home from research at the library, I will scoop up 3 - 5 ecommerce packages which my wife or mother-in-law have ordered (often baby supplies). The delivery fees for many of these packages will be <US$1.

Aside from the cost of living, China is very safe with almost no violent crime. Some of this is cultural, but a lot of it stems from the ubiquitous surveillance; probably my least favorite part of life in China, though many east Asian societies are ok trading in more security for privacy. The public spaces and parks in Shanghai are immaculate. The landscaping budget in Shanghai has got to be a not-insignificant portion of city GDP. As is well noted, public infrastructure is new and clean. Subway rides are generally a few RMB, so perhaps ~50 cents per ride. Public health systems are chaotic and crowded but generally efficient, high quality and affordable.

To be clear, this is not a "China rocks, the west sucks" expat porn piece. It's a portrayal of the relatively high quality of life in Shanghai at an extremely compelling price point, particularly if one earns in dollars. Arguably a severely depressed price point.

Lying Flat: Steamrolled by Deflation

I'm not oblivious. This affordability goes hand in hand with other societal costs.

The convenience I enjoy often stems from an abundance of migrant labor from the inland provinces doing tough jobs for low wages. The cost of rent is depressed because of the massive real estate slowdown. The infrastructure is fantastic but at the cost of overly stretched government finances. China's domestic demand engine is languishing at the same time its booming manufacturing sector is set to face greater geopolitical headwinds.

The challenges are numerous, and they are evident - even in outlier cities like Shanghai.

China has done an exceptional job of educating its populous over the last 25 years. The number of intelligent, technical, and hardworking young people emerging from Chinese Universities is the number one reason I remain bullish on the country. However, when facing a balance sheet recession, policy makers can either reach for the fiscal bazooka and risk inflation or stomach the deflationary shock and ensuing unemployment, a policy path which tends to disproportionately impact the young. To date, the leadership has erred towards the latter.

China has stopped reporting youth unemployment, but the vibes are not good. I have spoken numerous DiDi drivers with computer science degrees. I have spoken with local government employees whose application pipelines now include top graduates from Tsinghua or BeiDa. I have spoken with friends in Singapore from top Chinese Universities who mention large swaths of their graduating class had left the country. I have spoken with acquaintances that recently renegotiated office rents down in Beijing by 30 - 40%. There are signs that consumer sentiment is beginning to rebound but job prospects in this environment remain difficult for many. This, in turn, impacts household formation and only accelerates the already dismal demographic trends.

Looking around at the pristine infrastructure - not only in Shanghai and Hangzhou - but glistening new airports and high speed rail stations stretching from Yunnan and Guizhou in the west to Inner-Mongolia in the north, its easy to see how China could be at the tail end of a massive infra build-out, one it will be digesting for decades given the current debt load.

Many local government finances are challenged. The entire financial model of redistricting farm land for development will need to be revamped. There are decades of excesses. Digesting those excesses will take time. It will be painful. It has been painful. Even after the brutal correction, >50% of Chinese household wealth is tied up in real estate. The impact of the real estate slowdown to consumer sentiment will be long-lasting.

Incrementally, shifting towards an economy where domestic consumption plays a greater role would require difficult economic reforms. Such reforms would require a relinquishing of control from Beijing, ceding more capital allocation to households and private enterprises, which it is reticent to do.

These challenges are daunting.

However, 2025 was also the year I noticed a marked shift in sentiment on the ground in China; a quiet confidence which sparkled behind the eyes of my conversational counterparts - mostly young, technical, educated Chinese.

The Chinese Dream is Alive

To a person, almost all admitted the economic situation was difficult and many seemed surprisingly unexcited about their individual prospects, and yet basically every one of them was convinced of China's continued rise. It was less a question than a simple fact, a fact which might be slowed or accelerated by effective or ineffective policy but seemed, in their estimation, inevitable.

After a humbling three years of COVID shutdowns, a rising trade war, a real estate bust, an equity slump, and increasing state control, this confidence was striking.

The last three years were not another "China meltdown." They were a speedbump, growing pains in a continued rise.

There is less of the chest-beating, wolf-warrior-esque bravado of 2020-2021. This was quieter and self-assured. After proving China is the clear leader in renewables and electro-industrial manufacturing, can compete at the frontier of AI, and can go toe-to-toe with the US in a trade war, perhaps this is not surprising.

After three years in the doldrums, 2025 felt like a clear turning point in national sentiment for many elites. A quiet confidence that China is now the country building the future.

The Future is being built in China

One of the things that strikes me about the CCP is that it - like Peter Theil - has a much more salvific relationship to technology than the west. The CCP is racing to adopt and implement technology less out of platonic altruism than out of primal self interest. The race is existential. In a world without technological acceleration, China's rise will deflate and the CCP may lose a mandate stemming primarily from performance legitimacy. China is a middle income country with elevated debts and a rapidly shrinking population. China remains dependent on foreign sources of food and energy in a world where the seas are controlled by a geopolitical rival. Without astounding productivity gains, the model will implode.

Literally the only way to thread the needle is massive technological investment.

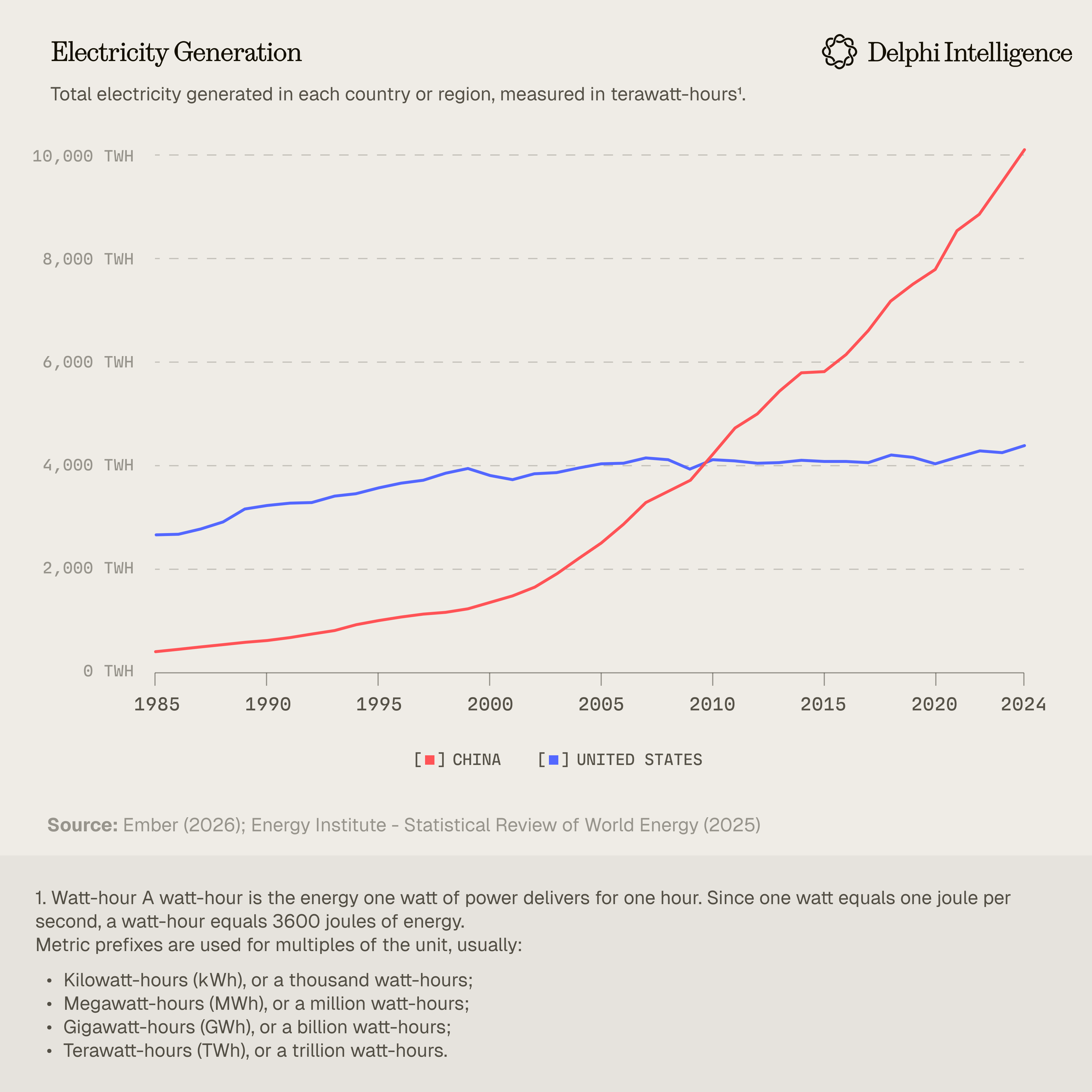

China is not building the future because it wants to. China is building the future because it must. Without the investments in nuclear and solar, China will be at the mercy of energy exporters. Without its own semiconductor ecosystem, it will be at the mercy of US export controls. Without its own payment rails, it will be at the mercy of US sanctions. Without automating its manufacturing sector, it will be at the mercy of shrinking demographics and rising wages.

While reindustrializing after thirty years of offshoring is a colossal undertaking for the U.S., these challenges are dwarfed by the challenges facing Beijing. The U.S. is protected by oceans and surrounded by allies. China has potential conflict on almost every border. The US is an energy and food exporter; China an importer of both. The US has legal and financial infrastructure to attract capital and talent from the far corners of the globe. China is largely limited to its domestic population, and even then, many of the brightest have the economic incentives to leave. China must revamp its economic and tax model while being unwilling to limit government oversight of the economy. China's Debt / GDP ratios are roughly equal to that of the US with a per capita GDP 1/5 as high.

This list goes on. I would not want to shoulder the burden of navigating a nation of 1.4 billion through these headwinds.

And still, despite all of that, China has a real shot at becoming world #1.

The U.S. is in the middle of blowing a 28-3 lead.

An Industrial Juggernaut

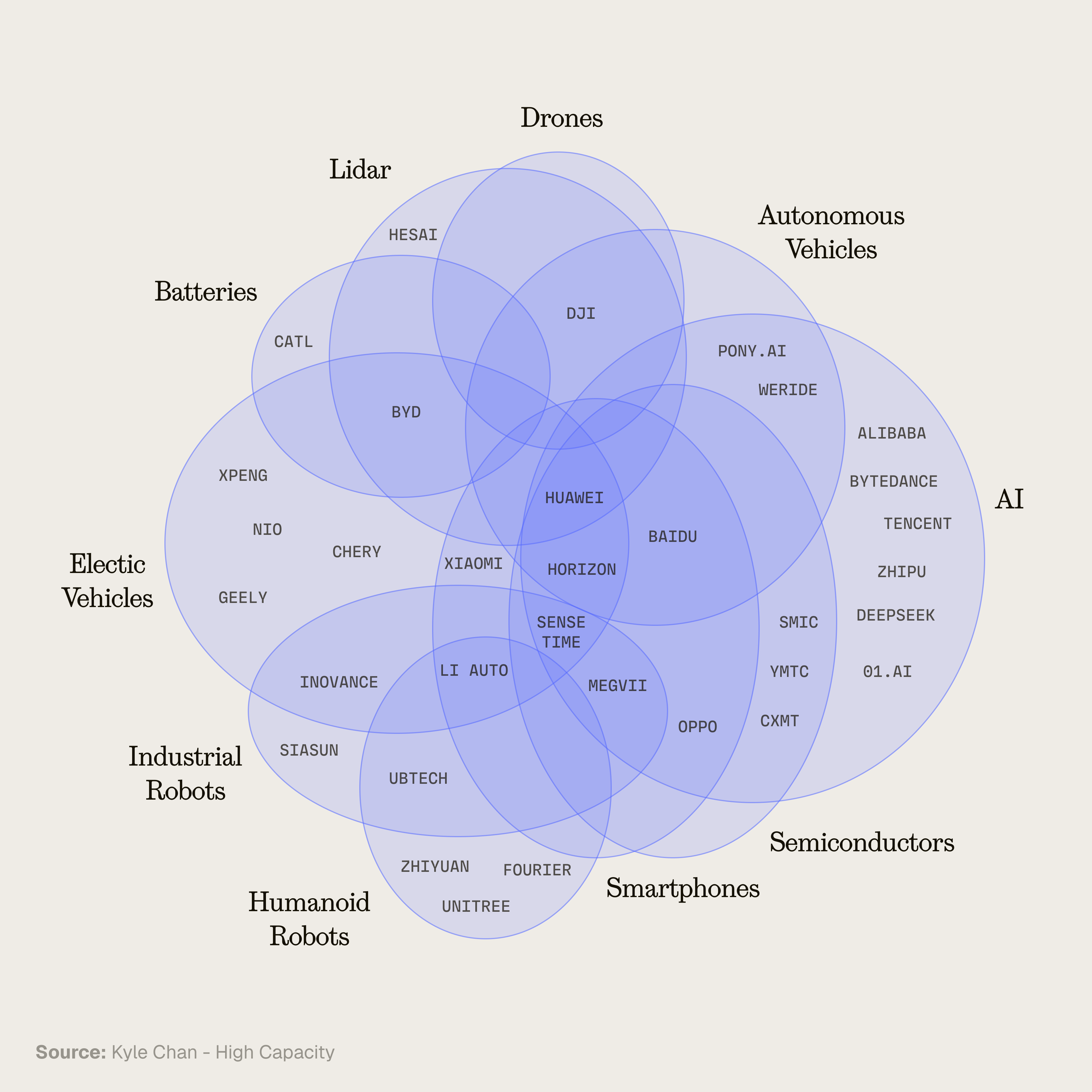

In almost every strategic value chain, China has been quickly ascending in global competitiveness. The 2020s appear to be the decade where China moves from capitalizing on low labor costs and imitation to capitalizing on systems-level superiority in many sectors.

While the system produces a lot of waste, Beijing's long-term strategic investments have often proven prescient, laying the groundwork for compounding gains in areas of national interest atop over-investment.

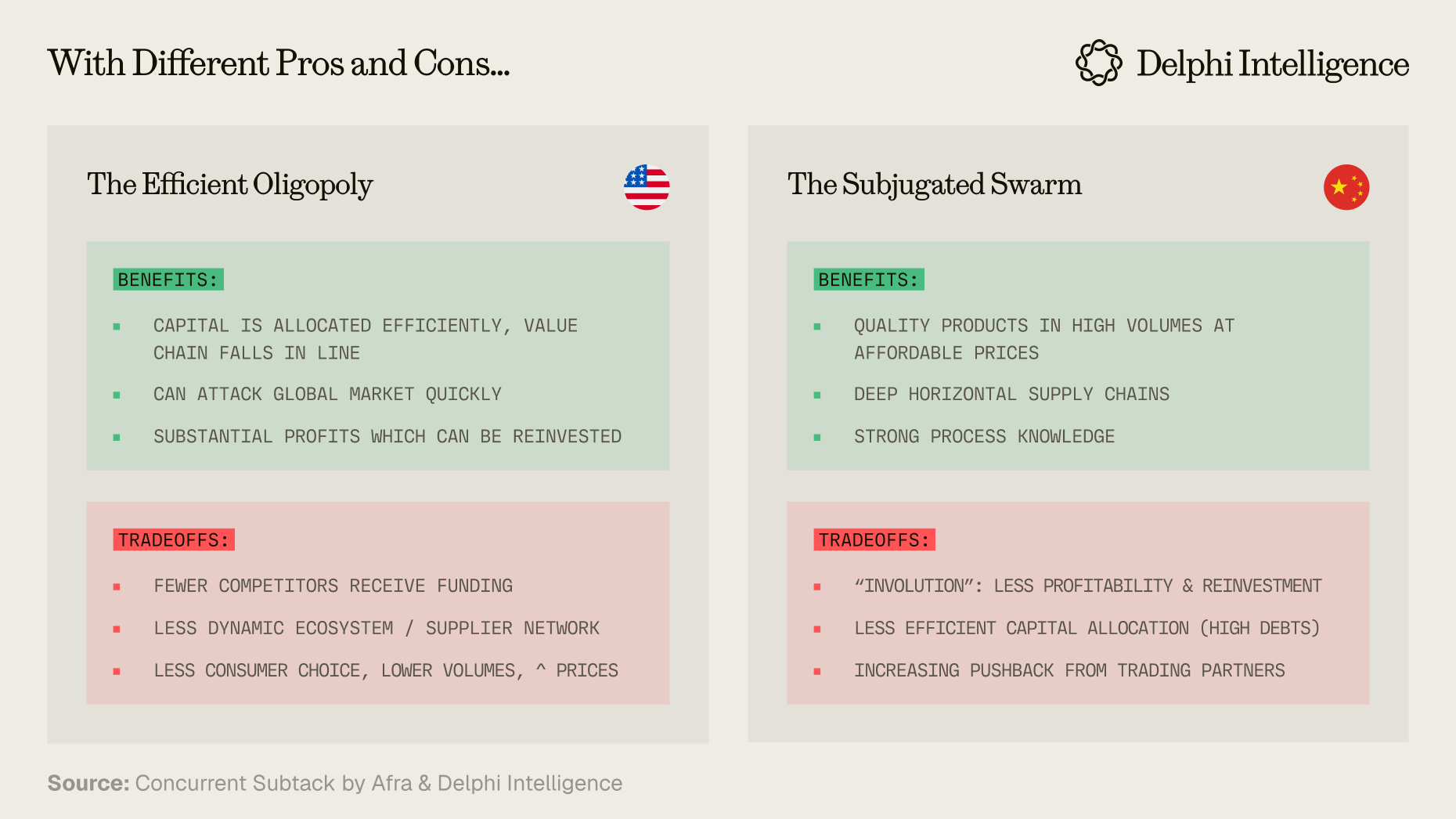

This contrasts markedly with the US approach which tends to king-make and vertically integrate much too early:

In many of these sectors, I can't help but feel that the Chinese government's continued reinvestment through incentives, subsidies, low wages, and a strikingly low exchange rate are operating almost like an Amazon at national scale; constantly forgoing profits and consumption, funneling export proceeds back into more factories, more competition, and more capacity - in a ruthless cycle of reinvestment.

This is happening across EVs, drones, biotech, and many more sectors where China is not only the low cost producer, but increasingly the lowest cost producer at frontier quality.

Of course, the pillar which underpins everything is energy. Cheap, abundant, ideally-domestically-produced, energy. The lifeblood of any industrial juggernaut and likely to be the defining bottleneck in the AI race:

Without protectionism, China would be poised to take significant share across a host of industries, compounding atop its public investments and swarm of cutthroat competition.

The obvious problem with this strategy, however, is that large trading partners are now fed up with deindustrialization at the hands of the industrial juggernaut.

Which is why I'm ultimately bullish on Chinese equities despite the regime's reticence of ceding control. Stimulating greater consumption and more robust capital markets are now aligned with its near-term goals amidst strategic competition with the US. We are starting to see this in the accommodative policy agenda. We are starting to see this with the anti-involution campaign. We are starting to see this in the bottoming of the RMB / USD exchange rate and a rerating of Chinese equities.

Given its rule of law, sturdy institutions, and deep capital markets, a premium on US assets is completely warranted.

But... a 5x premium in terms of % of global equities? Just seems likely the gap will close over the next decade.

Convergence: The Ensemble & The Soloist

I worked at a global Singaporean investment firm for a number of years. Every year, the organization would host a talent show, and the vast majority of years either the Chinese or the American teams would win.

The approaches couldn't have been more different. Inevitably, the Chinese would have broad participation in an intricately choreographed routine reminiscent of a mini-2008 Olympic Games Opening Ceremony in Beijing. These productions would clearly have taken a lot of time, energy and rehearsal, and they always went off without a hitch. The Americans, on the other hand, would send up a single representative who was abnormally talented. Limited participation, limited planning, just a soloist with stage presence. In many ways, it's was a microcosm of the two models.

However, I increasingly feel like the Chinese are developing their own virtuosos; individuals with the same ambition, vision and talent as a Steve Jobs or a Sam Altman, while the US is still struggling to rebuild its muscles for strategic planning and choreography.

Chinese entrepreneurs are constrained by their legal and financial infrastructure. American entrepreneurs are constrained by their industrial infrastructure.

To me, it seems the US has been in harvest mode for the past 25 years: milking its post-war legal institutions and deep capital markets for ever more juicy fruit while neglecting to invest in its foundations. Public education, research, and infrastructure are terribly mismanaged. Without investment in the foundations, the fruits will inevitably decay. China, on the other hand, has probably over-invested in its foundations, watering the roots again and again - often sacrificing near term harvests (higher wages, consumption, profits) for deeper roots.

But, of course, the US and China will end up becoming each other

Many will read this and call me a "Sinophile" and discount the message, so I will state my biases clearly.

I'm an American. I lived the first 27 years of my life in America. I'm pretty classically liberal and find many of America's founding principles beautiful and aligned with my view of human flourishing. Though imperfect, I believe America has been the most benevolent hegemon in world history.

Though I live in China, I prefer American culture. On average, I'm more comfortable with Americans. We share references, humor, an openness and optimism which feels like home. While I now have many Chinese friends, there is still more friction for me integrating into Chinese social gatherings. The settings are relatively more guarded, restrained somehow - especially early in a relationship.

I share this to say that I'm quite American. I think America is the greatest country on earth, and I hope she remains that way.

At the same time, the role of any writer is to tell the truth.

When I evaluate the tenants which underpin national power, China seems well positioned in several: the most obvious being industrial capacity and increasing technological preeminence. On both fronts, China has made strategic long-term investments - first in human capital and second in infrastructure - which will pay dividends for decades.

These long-term investments are beginning to show fruit; allowing Chinese companies to rapidly iterate their way to the frontier. This harvest may be accelerated by an open source approach to AI aiming to imbue commoditized, frontier-grade intelligence into its deep industrial ecosystem.

It is now clear that the US and China will decouple to the extent that they can, in core strategic areas at the very least. My assessment is that the challenges of decoupling were largely priced into Chinese equities over the last three years while they were neglected in US markets.

As it becomes clear that in decoupling, the two superpowers must converge, it means the relative size of their equity markets are likely to as well.

.png)